Executive Summary

Convergence of Telecommunications, Broadcasting and Information Technology is the engineering parallel of Globalization . Convergence has made it possible to digitize, transport, store, modify, retrace and distribute any kind of information and data over different kinds of infrastructure . This has led to the development of new markets wherein infrastructure networks and appliances are capable of carrying a host of services . The traditional separations between broadcasting , telecommunications and information have blurred in the new electronic communication markets and calls into question the logic of maintaining existing separate regulatory frameworks for each of them. The overlapping authority of separate regulatory bodies are causing confusion among new entrants, increasing transaction costs, leading to inconsistencies in regulations and more than often hampering the development of industry and technology . The task of framing new common regulatory regime which is coherent across the three sectors is complex as it requires review of law in all the three sectors. Secondly, the development of technology and markets depends greatly on how much the regulations take into account and foresee the future developments in the technology and the markets. The new developments call for a common regulatory agency across the three industries with horizontal separation in Broadcasting across content and carriage. The Countries across the world have responded differently and at different pace to Convergence . United Kingdom, Malaysia were the forerunners to form a single regulatory body to regulate the three sectors . The reform cycle in most of the countries started with privatization and corporatization of public operator, followed by establishment of a Telecom Regulator and later ended up with merger of separate regulatory bodies to form an integrated regulator. Singapore was the first country in world to form a specific telecom regulator in 1992. It later merged its telecom and IT regulator to form Infocomm Development Authority which has taken Singapore ahead in its vision to make it an ‘infocomm hub’ and ‘internet economy’. UK formed a single regulator- OFCOM and Malaysia formed Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission and simplified its licensing procedures. India has also taken a step ahead in forming a regulator and reforming its licensing systems. The benefits that can be reaped from the process of convergence are enormous both in terms of new offerings and in terms of new employment opportunities provided ‘Right Regulatory Structures’ are put in place. The countries that have responded by reforming earlier have been benefited the most and rest of the world should take lessons from them.

1.0 Introduction

ICT Convergence is to technology what globalization is to economy! Both are before us and are inevitable and unavoidable. Globalization of economies is an idea to integrate the world and let the free market forces drive the pulse of world. Whereas ICT convergence is a reality that has made it possible to digitize, transport, store, modify, retrace and distribute any kind of information and data over different kinds of infrastructure. Convergence refers to the process by which communications networks and services, which were previously considered separate, are being transformed such that:

· Any one network platform can carry all types of services whether audio, video, data transmission or voice.

· One integrated consumer appliance can receive all types of services, and

· New services are being created. Examples of new products and services being delivered include:

- Webcasting of any audiovisual services.

- Home-banking and home-shopping over the Internet,

- Voice over the Internet;

- E-mail, data , World Wide Web access and now television over mobile phone networks,

- use of wireless links to homes and businesses to connect them to the fixed telecommunications networks;

- Data services over digital broadcasting platforms ;

- On-line services combined with television via systems such as Web-TV, as well as delivery via digital satellites and cable modems;

2.0 Out Comes of Convergence

The fast and unbelievable developments in technology like increase in network speed, launching of new satellites with high transponder capacities, improvements in digital technology, compression techniques, miniaturization and advancement in storage capacities are behind convergence. Broadband Internet, 3G mobile networks, wireless LANs and digital televisions are the new platforms which are expected to play a key role in convergence in the forthcoming days . The newer technologies are continuously wiping out the line between broadcasting , telecommunication and internet as a service provider can now provide all types of services over his network which was not erstwhile possible.

Each aspect of convergence represented by the various circles in fig. 1 are beginning to overlap and the lines within each circle are now blurring more and more over time . The new services are becoming increasingly convergent capable of delivering all types of information - audio, video and text. On the other hand the delivery mediums and Customer Premises Equipments are capable of delivering and receiving all the types of services. Markets also have converged to offer a bundle of services in a package with one flat rate, there have been vertical integration of service providers and its now a one stop shop process. Ultimately, convergence would be characterized as a single circle

Modes of delivery of Service

Fiber/twisted pair- telecom operator

Fiber/Coaxial cable Power/Utility operator

RF Spectrum without satellite

Satellite

Market Related Developments

Bundling of Service

Flat rate price package

Integrated operations due to mergers/ condolidation/ linking

Power/Utility Service

Service Provider

Telecom Service

Cable Service

Broadcast Service

Power/Utility Service

Customer Premises Equipment

TV

Mobile handset

Computer

Fixed phone handset

Fig 1. Different Aspects of Convergence[1]

encompassing most of the portions of the individual circles. This blurring of traditional boundaries between telecom , broadcasting and internet calls into question the logic of maintaining existing separate regulatory frameworks for telecommunications, broadcasting and internet. These new developments do not mean that existing regulations need to extend their coverage over other platforms or services. However, the integration of frameworks is not simple and involves various issues as –

Ø It requires a thorough review of legal and policy framework of the three sectors and development of a single policy framework coherent across all the three sectors.

Ø Commercial success of a technology and market forces will determine the direction in which convergence takes and influence the environment within which policies must operate.

Ø At the same time the policies will determine the extent to which market forces are given sufficient leeway to come into play and facilitate the development of technology and market.

Thus governments across the world need to change the policy frameworks and regulations as per the market situations if they desire to realize the full potentials of these technologies for economic growth and social development.

The subject of this report is the identification of the right and best regulatory framework for dealing with convergence, and an attempt has been made to study the approach taken by United Kingdom, Singapore, Malaysia and India.

3.0 Convergence- Alteration in the effectiveness of Govt Policies

The government of each country has some social, economic and cultural objectives to serve through its policies. The economic objectives include encouraging investment and innovation, maximizing competition for the benefit of users and service providers and efficient allocation of spectrum to make communication, broadcasting and information sectors engines of economic growth. Social and cultural objectives include universal access to these services at affordable prices, plurality of voices in media, consumer protection and privacy, security of data and identity and above all the content should reflect the tradition and culture of the land. While convergence does not necessarily change governments’ objectives, it will influence the effectiveness with which existing policies meet those objectives. The trend across the world is to have separate policies for broadcasting, telecommunication and internet with separate regulatory bodies for each in most of the cases. Governments make use of a wide range of policies in the individual sectors varying in focus, reach and approach. They regulate the telecom sector through a Telecom Regulatory body which evolved out of the necessity of regulating the privatized public telecom operator. The various telecom regulatory bodies across the world work to define rules of competition, provide universal access across the country to the economically unviable regions, frame rules for newer services as they evolved with time and settle conflicts between various operators . Broadcasting sector is regulated in most of the countries by the Information or Broadcasting Ministry by issuing licenses for different types of services. The license conditions stipulate the content obligations, control the number of operators, size and influence of a particular broadcast media operator by restricting cross media operations and define the way of funding the public broadcaster .

But with time as the new technologies and services developed, the tight compartmentalization of policies, regulatory institutions and Ministries has become irrelevant rendering these formal structures ineffective. Convergence has intensified competition across delivery networks and between services for ex television is now available through number of delivery platforms- terrestrial, cable TV, DTH , internet and mobile telephone and there is increasing competition among the broadcasters and delivery platforms. Moreover there are a number of ways of audiovisual entertainment- television, video games, games over internet, programs and movies over CD/DVD intensifying the competition among services. The most distinguishing outcomes of convergence is development of new services like IP TV, interactive Cable TV etc which has led to spectrum crunch shooting up the spectrum cost and costs of regulating it. The nature and type of new services often do not fit easily into the existing regulatory definitions and frameworks. For ex. if audio-visual content is offered through Internet the dilemma regarding its regulation crops up. Should this be considered as a telecom service or a broadcasting service? And how should it be regulated- by a Broadcast Regulatory Authority or by a Telecom Regulatory Authority? What if the origin of the content is not national? The technology is too complex often to identify the source of content . The global nature of the Internet and satellite-delivered services point to the potential difficulties of enforcing the rules of one country in other countries . The rapid pace of change in terms of services and products measured in months and weeks also present a real challenge for anyone seeking a legislative solution to any particular problem. The governments are trying to cope up with the changing times by restructuring the policies and regulatory institutions but the uncertainty as to where commercial and technological forces will lead and the pace with which these changes will occur is making the task for governments complex in terms of assigning priorities to reforms. Unnecessarily restrictive policies could inhibit the development of these services and the associated benefits to consumers and the economy. The existing structural rigidities, the socio political state of the country, and the determination of the government will determine the pace of change. Governments of Singapore, Malaysia and UK have emerged as leaders in restructuring their regulatory frameworks to take mileage of ICT Convergence in fostering their economic and social objectives.

4.0 The Normative Regulatory Framework

The new regulations need to be designed meticulously to meet the challenges & make the best out of opportunities offered by convergence . The old "one to one correspondence" between Regulatory body and the type of service is no longer true. On the contrary, since each technology can deliver a plurality of services and each service can be delivered by a number of technologies there should be only one regulator to regulate and guide all technologies, service delivery platforms, services and common markets. Also, the nature and characteristics of convergence as well as the perceived need of industries call for limited regulatory intervention . A more direct emphasis should be given to regulations based on the market characteristics of each specific service rather than on its delivery system (service based Vs carrier based regulation). This choice should allow to avoid the common mistake of mechanically applying or extending existing regulations to new services. According to this approach, the market characteristics on the supply and the demand side of the specific service would originate the type of regulatory intervention. On the supply side a plurality of delivery systems seem to characterize many of the convergent services (for instance, Broadcasting can be offered through satellite, cable, radio links, etc.). At the same time, because of budget and time constraints, the demand side of many converging services will be characterised by a substitution effect among services, thus, making, very often, the service provider to be a ‘price taker’ rather than a ‘price maker’.

The task of defining an effective and very specific regulatory framework for the converging environment - where the potential to set up new services whose life-cycle is unpredictable, but very often quite short – may become an impossible one. It seems more reasonable to define flexible and general regulatory principles, acting as "regulatory guidelines", and assign to market forces the task of crafting the new environment. The new regulations should be as flexible as possible and should quickly move towards a situation where specific ex-ante regulation are applied only in case of lack of market self-regulation or complete market failure. They need to take care of few things like:

Ø Optimum utilization of spectrum to cope up with the excessive demand pressures on spectrum. Options like secondary trading of spectrum or handing back of excess spectrum should be kept open.

Ø The regulatory framework in broadcasting should be structured horizontally i.e carriage and content should be regulated separately in place of existing vertical framework structured along industries. This allows changes to the regulations of carriage & content to occur at a different pace as the uncertainty surrounding convergence is greater on carriage side.

Ø Regulations on content should be mainly driven by the social & cultural objectives of a country. The level of regulation applied to a particular service could be influenced by the level of interactivity & the degree of control or choice which can be exercised by the viewers.

Ø There should be a common regulatory regime for carriage of all communication, broadcasting & information services . The main objective behind this regulatory framework should be to do away with the current monopolies & would require governments to continue on the existing lines of liberalization in telecommunication sector applied further to broadcasting & internet. This approach would free the markets to work and the best of technology and services will survive and flourish.

Ø Vertical integration can be considered as an opportunity to stimulate the growth of the emerging markets. The stress should be on regulatory structures to avoid the abuse of dominant position.

In this scenario a revision of the nature and role of different Regulatory Authorities might be necessary. The converged market demands a single Regulator in charge of controlling together Telecommunications, Broadcasting and Information Technology markets.

In a world where service provision increasingly crosses national boundaries, with the appearance of world-wide operators offering integrated multimedia services, it is essential to ensure that the national regulatory approach is compatible with the international framework. In this perspective, the creation of national Regulators should take into account the ongoing world-wide globalization process. So new regulatory model should be progressively introduced to prevent a disruptive change and ensure compatibility with the other countries.

5.0 Regulatory response to Convergence across the world

While technology may be bringing telecommunications, broadcasting and the Internet closer together, the regulatory frameworks within which the industries operated remained not only quite separate but also focussed on different objectives until recently. In past three decades the growth of telecommunications, broadcasting and internet has led to establishment of number of regulatory agencies within countries, targeted specifically at different aspects of individual industries. The countries have started responding to globalization by reforming as they privatize, liberalize and deregulate their telecom and broadcasting sectors. Over the last decade, the drive to liberalize the telecommunications market has seen development of regulatory frameworks aimed to stimulate the roll-out of new technologies and services and to manage the transition from monopoly to competition. While most countries have adopted sector specific legislation and independent regulators, the medium term objective of these countries is to move eventually towards greater reliance on general competition law. The major influences underlying the regulation of broadcasting, on the other hand, have been the social and cultural impact of the industry and the shortage of spectrum. Broadcasting remained highly regulated. Although significant changes have taken place in the broadcasting environment and internet due to convergence at the technological and service level, the emphasis in changing regulatory frameworks has not been as pronounced as for telecommunications.

The countries are now reforming towards creating an independent regulatory agency to govern the ICT sector as a whole and to empower them to deliver effective regulations and policies to facilitate development of technologies and markets. The success of this reform process depends on the way countries approach to create these regulatory bodies and their independence from the influence of government and business houses. Only six of the 30 member countries of OECD(Canada, Italy, Japan, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States) give responsibility for broadcasting and telecommunications to the same regulator (or Ministry in the case of Japan). But, for most of these countries, broadcasting and telecommunications have separate legislation. Among these countries the United Kingdom has finalized legislation to create a single regulator for electronic communication services, Office of Communications (hereafter OFCOM) , subjecting the sector to a single Act, the Communications Bill.

A number of non-OECD countries have also moved in this direction. For example, Israel has decided to establish the Israeli National Regulatory Authority with responsibility for the telecommunication and broadcasting sectors. The new body will merge the three current regulators (Ministry of Communication, the Cable and Satellite Broadcasting Committee and the Second Authority for Television and Radio). Malaysia and Korea have taken steps towards single regulator. India has taken steps to have unified licensing system so as to regulate carriage related issues through a single regulator – ‘Telecom Regulatory Authority of India’ and discussions are on way to have a separate content regulator which is presently being looked after by Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. The events and changes in respect of Singapore, UK, Malaysia and India and are briefed in this section below

5.1 Singapore

Singapore is a small country located at a strategic location in south east Asia and is one among the four East Asian Tigers well known for their high economic growth and development. It is a service oriented economy ranking sixth in per capita GDP in the world. The government of Singapore is determined to take economic mileages from info-communication by putting in place a right regulatory framework that would attract multinationals and would benefit local business through faster & well connected business and presence of potent MNCs. Singapore was the first country in the world to create a sector specific telecom regulatory body in 1992 ‘ Telecommunications Authority of Singapore’ . In mid to late ’90s TAS implemented the gradual and phased introduction of competition through the licensing of services that were progressively liberalized. Singapore established an agency-‘ National Computer Board’ to make Singapore an ‘intelligent island’ through pervasive development of computing and IT, increased stress on developing computer literacy and creating an IT culture across the country. The government of Singapore has adopted the term info-communications to convey the concept of computers, content, and transmission as a converging whole. The various regulatory bodies Telecommunications Authority of Singapore, National Computer Board , Economic Development Board and occasionally Singapore Broadcasting Authority had overlapping authority with regard to information, broadcasting and telecom regulations, promotion and development resulting in duplication of resources and efforts. The two independent bodies TAS and NCB were merged to form a single body IDA in Dec ’99 and were placed under the Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Technology. The rational behind the merger was to have a single government agency for policy formulation, regulation and development of the IT and telecommunications sectors[2]. IDA was created to perform three distinct functions that the government viewed as complementary and compatible:

1) Regulatory and policy-making functions;

2) Promotional, industry development and public outreach tasks; and

3) Logistical/technical support, as the manager of IT and network systems for all of Singapore’s government ministries, independent agencies and other office.

The earlier plans for merger included merger of Singapore Broadcasting Authority (hereafter SBA) also in IDA to take cognizance of the fact that a number of multimedia services (both audio and video) would be delivered on converged delivery platforms like internet and broadband. But SBA had a unique function of regulating content which is sensitively linked to the cultural identity of the nation and hence the government failed to gather enough support to do so.

In Dec2001 in anticipation of the next phase of convergence between IT, telecommunications and broadcasting, IDA was moved to the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts (MITA) to be side by side with the Singapore Broadcasting Authority (SBA). Presently the two authorities IDA and SBA function independently and in close coordination at all formal and informal levels. While the IDA regulates and promotes the development of broadband network and oversees internet access services, SBA regulates the content that is delivered over those networks to ensure that it is in conformity with the codes of practice and standards.

IDA has a CEO office under which various groups looking after varied functions operate namely Policy and Competition Development Group, Infrastructure and Manpower Development Group, Industry Group, Technology and Planning Group, Government Systems Group and Corporate Development Group. IDA has two subsidiaries Infocomm Investments Private Ltd(IIPL) and Singapore Network Information Centre(SGNIC). IIPL is a wholly owned subsidiary of IDA formed with an aim to effectively use equity investments of IDA to make Singapore an Infocomm hub. SGNIC like IIPL is also a wholly owned subsidiary of IDA which administers the internet domain name space ‘.sg’.

The first function of IDA as it was formed was to implement the introduction of full competition in telecommunication sector that was planned to begin from April 01, 2000. In years to follow IDA further facilitated competition, established a regulatory framework for interconnection and competition by drafting regulatory ‘Code of Practice’. Singapore is implementing a master plan named ‘ InfoComm 21’ that is designed to transform the country into a thriving and prosperous Internet economy by 2010. The major pillars of the plan include strategies to use Infocomm for enhancing connectivity, creativity and collaboration; develop Singapore’s hub status in digital medium for distribution and trade; grow new economic activities and create jobs as engines of growth in areas like value added mobile services, wireless and wired networks, multimedia processing and management; expand web services and portals ; expand securities and trust infrastructure and use Infocomm to build efficiency in business and government agencies.[3] The important aspects that hall mark this program are the governments approach to ICT issues[4] -

Ø Government can and should act as a catalyst of market change and growth;

Ø Private sector and Public sector forces can work in tandem to achieve goals;

Ø Singapore must attempt to be in most competitive in most, if not all ICT industries;

Ø Industry regulation is just one tool, among several, that government can use to establish market conditions conducive to growth and competition.

IDA had since its inception been always applauded for its key role in the development of Singapore. It has been successful in its role as a regulator and as a facilitator in promoting and developing country’s communication capabilities and industries to make it a “ Info-Communication Hub”.

5.2 United Kingdom

In Britain the reforms cycle was similar to that of Singapore starting with privatization of the Public telecom operator ‘British Telecom’ and creation of a telecom regulator ‘OFTEL’ followed by gradual liberalization of telecom market and concluding with a single regulatory agency. OFTEL was established to ensure that the new private operator does not misuse its market power through regulations on tariff, interconnection guidelines, service standards, international accounting agreements etc. But the span expanded with time as newer technologies developed to include regulations for cellular operators, cable TV, data protection over networks and issues relating to convergence. The broadcasting industry also saw establishment of various regulatory agencies depending on the pressing issues with time -

- British Broadcasting Corporation 1920

- Cable Authority created in 1984 by Cable TV Act to regulate and promote cable industry. It was later merged in Independent Television Commission in 1990.

- Independent Broadcasting Authority to establish programming guidelines

- Broadcasting Complaints Council (BCC) created in 1981 to investigate violation of rights of third parties; later renamed Broadcasting Standards Commission and merged in OFCOM.

- Broadcasting Standards Commission(BSC) established in 1988 to enforce decency and standards of good taste for content

- Radio Authority to regulate commercial radio broadcasting.

Thus there were a number of regulatory agencies working in specific areas. Though new agencies were created and merged with time it was realized that convergence has increased competition which has made a number of rules obsolete and the industry is facing confusion and conflicts due to different agencies giving directions on similar issues and same services. In response to convergence the government of UK came out with a white paper realizing the need for a set of coherent rules across the three sectors describing objectives as[5] –

· to ensure the widest possible access to a wide variety of communications services;

· to safeguard the interest of citizens and consumers by protecting them from poor service delivery and overcharges;

· to host the most dynamic and competitive communications environment in the world;

· to maintain the country’s competitive advantage in the international market place;

· to promote access to the internet and higher bandwidth services; and

· to protect media plurality.

The Communications Bill ‘2000 called for establishment of an integrated regulator- OFCOM with an aim to enhance pace and quality of decision making. Consultation Process on white paper was carried out to get the opinions of individuals and organizations on the issue and impact assessment exercise was done to outline the advantages and disadvantages of a single regulator. OFCOM was created by merging five separate regulatory bodies which had overlapping authorities[6]-

-OFTEL

-Radio Communications Agency

-Independent Television Commission

-Radio Authority

-Broadcasting Standards Commission

The new regulations simplified rules governing telecom, radio and television services and relied more on market to develop tendency of self regulation among the industries. Content regulation is also within the purview of integrated regulator in UK unlike that in Singapore and India. Before the new law content was regulated by two separate bodies ITC- to set the standards and BSC- to monitor compliance. BBC and internet however are not in purview of OFCOM as BBC is to be governed by BBC Governors . However, BBC and other broadcasters are required to follow OFCOM guidelines and standards in areas such as decency. Secondly, once UK goes digital and completely withdraws analog technology envisioned to be done by the end of the decade the delivery platforms that BBC would be using would be OFCOM regulated mediums. Internet exclusion is also for name sake as the delivery and access mediums are all OFCOM regulated. Internet is regulated by the Department of Trade and Industry for commercial matters and Law enforcements for criminal matters. Regulation of spectrum is also under the authority of OFCOM which is required to be carried out as per European Union guidelines to ensure best utilization of the resource.

Thus Britain has transited from a number of regulatory bodies to a single

body in response to converging technologies and was one of the pioneers in reforming

with time to get the best out of technology..

5.3 Malaysia

Malaysia is another example which has been benefited by early planning to greet convergence. Malaysian government welcomed ICT convergence as an opportunity to use ICT for economic and social development. Malaysian telecom reforms were similar to Singapore, United Kingdom, India which began with the privatization and corporatization of public telecom operator (1987) and establishment of a telecom regulator. The Jabatan Telecom Malaysia ( Dept of Telecom) then became the telecom regulator and National IT Council was established in 1994 to look on the policy matters pertaining to IT. Broadcasting was governed by Broadcasting Act 1988 and implemented by the Information Ministry. In 1989 Malaysian Prime minister issued Vision 2020 that inspired projects like Multimedia Super Corridor which included seven initiatives like electronic government, telemedicine, smart cards, smart schools, R&D Clusters, world wide manufacturing web and borderless marketing ; all these required a thrust on ICT and multimedia. With advancing technology government realized obsolence and insignificance of the tightly compartmentalized regulatory framework and the system of issuing numerous specific licenses[7] . To make their vision successful a new act the 1998 Communications and Multimedia Act was made to integrate the three sectors in regulations which repealed the earlier two acts. The communications and Multimedia Commission was formed as a single regulator whose functions was to regulate the communications and multimedia industry based on powers provided in the Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Act(1998). The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission is also charged with overseeing the new regulatory framework for the converging industries of telecommunications, broadcasting and on-line activities[8]:

Economic regulation, which includes the promotion of competition and prohibition of anti-competitive conduct, as well as the development and enforcement of access codes and standards. It also includes licensing, enforcement of license conditions for network and application providers and ensuring compliance to rules and performance/service quality. Technical regulation, includes efficient frequency spectrum assignment, the development and enforcement of technical codes and standards, and the administration of numbering and electronic addressing. Consumer protection, which emphasizes the empowerment of consumers while at the same time ensures adequate protection measures in areas such as dispute resolution, affordability of services and service availability. Social regulation which includes the twin areas of content development as well as content regulation; the latter includes the prohibition of offensive content as well as public education on content-related issues.On 1 November 2001, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission also took over regulation of the Postal Industry and was appointed the Certifying Agency pursuant to the Digital Signature Act (1997). The MCM Act recognized four types of licensing categories based on services – Content application service provider, Application service provider, Network service provider and Network facility provider and made provision for issue of individual and class licenses based on the level of regulatory control desired. Class licenses are issued for services requiring lesser controls. Cross Ownership of companies was allowed thus facilitating the companies to go ahead with creative business. The beauty of the law lies in its flexibility to adapt to changing uncertainties of technology, business and market and its way of encouraging self regulation. The action of Malaysia helped meet its vision to create a highly connected society.

5.4 India

5.4.1 Growth of the three sectors:

The growth rate achieved in teledensity in telecom sector in fifty years was to the tune of 1.52; a rise in teledensity from a figure of 0.02 in 1948 to a figure of 1.94 in 1998. This was the period of monopoly of government i.e. Department of Telecommunication in providing telecom services in the country. The reform process started with National Telecom Policy 1994(NTP’94). Telecom Regulatory Authority was set up in 1997 but the first tariff order was issued in 1998 –thus reforms were effective from 1998. The revised National Telecom Policy issued in 1999 further pushed the growth and since then India never looked back. The teledensity growth in last two years 2003-04 and 2004-05 was 2% same as that achieved in fifty years. The growth started in first phase (1998-2003) of reforms and was further pushed in second phase (2003-05) which was mainly mobile driven. The third phase of the reforms is expected to generate a growth of at least 4.5%. The following graph[9] give a comprehensive picture of the telecom growth in India. India is today the sixth largest telecom network in the world. The subscriber base for telephony services continues to maintain a high growth and in May 2005[10] the number of total fixed lines were 47.11 million and number of mobile subscribers was 55.38 million taking a total subscriber base to 102.49 million. This is projected to increase to 175 million by 2010. The teledensity is also expected to grow from 9.17 in May 2005 to 15 by 2010. The growth in internet, broadband and other internet based services has been substantial and there is a huge growth potential in this sector. The internet subscriber base has grown from 4.99 million in FY 2003-04 to 5.55 million in 2004-05. The growth rate had been 21% in FY 2004-05. It is expected to reach a figure of 18 million by 2007 and 40 million by 2010. The broadband subscriber base has risen from 0.2 million in FY 2004-05.

Fig. Teledensity in India

Broadcasting industry has also developed in last thirty years and radio and TV cover almost every piece of Indian land now. The sector was a government monopoly till 1991 when only All India Radio and Doordarshan- the public broadcasters were allowed to operate. In 1991 satellite TV was opened to private sector to be distributed through cable. Since then the satellite and cable TV has developed greatly and the recent National Readership Survey 2005 has revealed that the number of TV house holds has increased to 108 million house holds which is more than 50% house holds in the country an increase of 32% over that in 2002 .Radio and TV through DTH is the latest introduction in Indian broadcasting scene. A snapshot of telecom reforms and regulatory transitions have been given in Exhibit 1 and 2.

5.4.2 Regulatory Framework and Reforms

There is system of issuing separate licenses for operating different services based on technologies like mobile, WLL, basic telephony, internet, satellite communication, Private FM radio, Satellite TV Broadcasting etc. Internet sector faced little or no regulations. The various sectors were liberalized with time. In telecom there was monopoly of Department of Telecommunications in providing basic services. In the year 1992 licenses were given to two private operators in each circle[11] to commission GSM technology based mobile services (the govt operator was not allowed to enter the GSM market). In 1994 the basic telephony sector was opened and licenses were issued to one private operator in each circle . Later BSNL was allowed entry in GSM in 2002 and a fourth private mobile operator was also allowed . Broadcasting witnessed opening up for private sector in FM Radio, satellite radio/ TV and DTH . TRAI is now under consultation for provision of private terrestrial TV and digital cable TV. India also realized the increasing difficulties with separate licensing as the sectors converged technologically .

The need to reform and modernize the regulatory framework in response to convergence was felt in India for long; but received a policy attention in 2001 when on 17 January 2001, the Indian Group of Ministers (GoM), chaired by Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha, formally approved the draft of the nation’s Communication Convergence Bill (CCB). The most significant component of the Bill was its creation of the Communications Commission of India (CCI), which theoretically would act a super regulator overseeing telecommunications, broadcast and information technology. It was anticipated that the regulatory Bill and Commission would facilitate an inclusive and stable institutional framework sensitive to the most current needs of a dynamic mass media and information technology market. The policy approach of combining formerly distinct communication sectors in a united structure was expected to provide for increased transparency. The Bill proposed to replace large number of categories of license with the following five broad categories to enable service providers to offer a range of services within each category, namely: -

(a)to provide or own network infrastructure facilities; (b) to provide networking services;(c) to provide network application services;(d) to provide content application services;(e) to provide value added network application services

The bill however failed to become a law because CCI was proposed as a super regulator, law could not get rid of license raj and there were conflicts between Ministries of Communication and Information- Broadcasting over regulation of content and dubbing audio-visual media with print media etc.

The attempts to make regulatory provisions to accommodate convergence continued and the Dept Of Telecommunications vide its notification dtd 9th Jan 2004 had notified Broadcasting services and Cable Services to be under Telecom Services and they were brought under the purview of TRAI. Since then TRAI has come up with consultations and subsequently recommendations on Cable TV Interconnect Agreements, Broadcasting and Distribution of TV Channels, Private FM Radio Broadcast licensing, Issues related to Satellite Radio Service etc.

Next step for TRAI was to move towards a system of unified licensing and it issued draft recommendations for Unified Licensing regime in 2003 with a key objective to encourage free growth of new applications and services in ICT. Other main objectives of the Unified Licensing Regime are:

· to simplify the procedure of licensing in the telecom sector,

· to ensure flexibility and efficient utilization of resources keeping in mind the technological developments,

· to encourage efficient small operators to cover niche areas in particular rural, remote and telecommunication-facilities-wise less developed areas, and

· to ensure easy entry , level playing field and ‘no- worse off’ situation for existing operators.

Government accepted TRAI’s Unified Licensing recommendations which envisaged a two-stage process to introduce a Unified Licensing regime in the country. The first phase that entailed a Unified Access Service License at Circle level has already been implemented. Once the broad framework was decided and put in place, the TRAI began consultation on the implementation of second phase of Unified Licensing Regime. A preliminary consultation paper and subsequently a final consultation paper were issued to obtain comprehensive inputs from all the stakeholders. Open House discussions were also held in this regard. Based on the comments received in the Consultation process and its own analysis TRAI has finalised its draft recommendations of second phase of ULR.

Salient features of TRAI’s recommendations are as follows( also tabled in Exhibit 4):

i) Framework of Unified Licence :

a) There shall be four categories of licenses:

1.) Unified License - All Public networks including switched networks, irrespective of media and technology, capable of offering voice and/or non-voice (data services) including Internet telephony, Cable TV, DTH, TV and Radio Broadcasting shall be covered under this category. Unified licensing implies that a customer can get all types of telecom services from a Unified licensing operator.

2.) Class License - All services including satellite services, which do not have both way connectivity with Public network, shall be covered under Class license. This category excludes Radio Paging and PMRTS Services and includes Niche Operators.

3.) Licensing through Authorization - This category will cover the services for provision of passive infrastructure and bandwidth services to service provider(s) of Radio Paging, PMRTS, Voice Mail, Audio Text, Video Conferencing, Video Text, Email, UMS, Tele Banking, Telemedicine, Tele- education, Tele Trading, e-commerce, other service providers as mentioned in NTP99 and Internet Services including existing restricted Internet telephony (PC to PC; within or outside India, PC in India to telephone outside India, IP based H.323/SIP terminals connected directly to ISP nodes or similar terminals within or outside India), but not Internet Telephony in general.

4.) Stand Alone Broadcasting and Cable TV License- This category shall cover those services providers who wish to offer only broadcasting and /or cable services.

Main features are:-

· Unified Licensing regime introduced for all telecom services to encourage free growth of new applications and services.

· Revenue share License fee presently up to 15% of Adjusted Gross Revenue (AGR) reduced to a maximum of 6% of AGR, with no revenue share and/or entry fee for a number of services.

· A licensee shall be able to provide any or all telecom services by acquiring a single license.

· Customers can get all telecom services including voice, data, Cable TV, Direct To Home TV, Radio broadcasting through a single wire or wireless medium from a Unified license operator.

· Internet Telephony including IP enabled services allowed to Unified License and Niche Operators.

· Nominal Registration charge (Rs.30 lakhs) for Unified License .Migration optional at this stage. Mandatory after 5 years.

· Service specific licensing regime permitted to be continued till two years of implementation of Unified Licensing regime.

· After two years of the date of implementation of these recommendations all new service providers shall be licensed under new Unified licensing regime.

· Niche operators without any entry fee permitted to operate all services in rural/remote areas (less than 1% teledensity areas).

· To offer ‘Broadcasting Service’, the Unified licensee will have to apply to I&B Ministry in case such clearance is required and fulfil other requirements as prescribed.

The ULR shall be definitely boosting the ICT industry and market as a whole. The important factors that still need to be considered to boost telecom in India in coming time are the weak demographics i.e skewed rural-urban population mix, income distribution, skewed connectivity in urban areas. For maintaining further growth of telecom services India has to increase the teledensity in the already covered urban areas and increase the exposure of rural areas. For this a decreased entry cost and tariff is necessary.

Indian step towards reforming licensing system seems to be promising and as it moves away from multiple licenses the cost of providing services will reduce benefiting the consumers, service providers and facilitating the development of market. The participatory style of framing policies has so far been very successful . India’s strong position in the world in software industry, BPO services and higher technical education will be boosted by better and cheaper services in ULR. The country will surely be advantaged by the reduced rigidity and proper institutions in new regulatory system.

6.0 Conclusions

The benefits that can be reaped from the process of convergence between information processing, telecommunications and television are enormous both in terms of new offerings and in terms of new employment opportunities. The most important thing to get maximum benefits is to put ‘Right Regulatory Framework’ in place. The regulations should be minimal and should evolve from the industry itself as ‘ code of conduct’. The Regulator’s task should be limited to issuing guidelines but should ensure to correct any information asymmetry and check market failures. The countries like Singapore, UK and Malaysia who had clear visions of future development have been advantaged most by putting in place a good regulatory reforms and the fruits that ULR will bear in India are promising and yet to come. It can be concluded that a good regulatory system is the focal point and those across the world who refine their regulatory structures in response to convergence would definitely be paid back well by technology and markets.

References:

1.) Implication of Convergence for Regulation of Electronic Communications ’ OECD 12/07/04 paper by Directorate for Science Technology and Industry.

2.) Telecom Regulatory Authority of India –The Indian Telecommunication Services Performance Indicator Jan-2005. (website- www.trai.gov.in)

3.) OECD: Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry / Committee for Information, Computer and Communication Policy-Working paper on ‘The Implications of Convergence, July, 12 2004.

4.) TRAI Study paper 2/2005 ‘Indicators for Telecom Growth’.

5.) Green Paper on the Convergence of the Telecommunications Media and IT Sectors , and the Implications for Regulations towards an Informational Society Approach- European Commission, Brussels, 3 December 1997

6.) ITU- Telecommunication Development Bureau :Regulatory impact of the phenomenon of convergence within the telecommunications, broadcasting, information technology and content sectors.( Ques 10/1 dtd 6/9/01)

7.) Regulatory responses to Convergence- Study on four countries. Paper by Martha Garcia Murillo - The Journal of Policy, Regulation and Strategy for Telecommunications, Information and Media, 2005 Vol7, Issue 1.

8.) Official websites of IDA, OFCOM, MCMC, TRAI.

9.) OFCOM- Information- Convergence and Never Ending Drizzle of Electric Rain by Stuart William. International Journal of Communications Law and Policy Issue 8, winter 2003/04.

10.) Effective Regulation – Case Study Singapore 2001, International Telecommunication Union

[1] Telecom Regulatory Authority of India - Unified Licensing Regime recommendations, www.trai.gov.in

[2] www.ida.gov.sg website of IDA

[3] see IDA website for details.

[4] See ITU case study on Singapore for details

[5] Martha Garcia Murillo 2005

[6] for details see Martha Garcio Murillo 2005

[7] For details see Martha Garcia Murillo, 2005

[8] Website of MCMC: www.mcmc.gov.my

[9] TRAI study paper no. 2/2005 ‘Indicators for Telecom Growth’

[10] Figures as per TRAI

[11] For telecom operations the country is divided in circles based on the political division of states

Sunday, January 28, 2007

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

BRIDGING THE DIGITAL DIVIDE IN INDIA - LESSONS FROM EGYPT

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

India, the second largest populated country of the world, is predominantly rural in nature. Despite 72% population living in rural areas, the socio-economic conditions of most of the villages have been pathetic. Absence of basic telecom infrastructure and suitable policy initiatives has hampered addressing of issues like literacy, primary health care, rural banking etc through Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). The ICT sector is one of the prime support services needed for rapid growth and modernization of various sectors of the economy and is also vital for social development of the country. The same was well understood by policy makers in India and was iterated in the Indian Telecom policies of 1994 and 1999, which envisaged a conducive and enabling environment to facilitate the country’s vision of becoming an IT super power. In 2005, if we look back, we will find that many of the targets set by these policies have been achieved in totality but, a deep insight into the facts and figures will reflect a glaring disparity between rollout of ICT services in urban and rural India. The writing on the wall is clear. The implementation of new telecom policy has left India divided – digitally. Therefore, it is vital that an enabling environment through policy and regulatory measures is created for the transformation of the existing digital divide into digital opportunity, which also has been a key driver behind the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS).

In such a scenario it becomes necessary for India to look towards some of the developing countries which are similarly placed as India and draw lessons for developing the ICT facilities in rural and remote areas at lowest possible costs. The growth of ICT in urban India has been mainly demand driven. But, increasing the penetration of ICT in rural India will require greater effort on supply side i.e. policy initiative from state. Scanning the world horizon, we find that despite economic slowdown, Egypt rose strongly in ICT diffusion ranking from 154th position to 112th position worldwide mainly because of policy leadership in areas of building public-private collaboration in ICT deployment.

This policy paper analyzes the reasons for skin deep telecommunication revolution in India and groups the efforts made in India to bridge the digital divide. It explores the effectiveness of Egypt’s policy initiatives for ICT diffusion like “PC for community” and “IT Clubs” and recommends how such initiatives can be customized and replicated for bridging the digital divide in India.

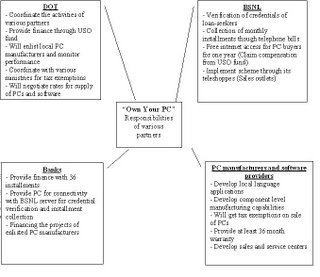

“PC for Community” policy offers affordable, Internet-enabled computers payable through installments, with telephone line as a guarantee and no requirement of deposits. The computer hardware is provided by various manufactures, finances are provided by major banks and the telephone line provision and installment collection is done by Telecom Egypt (TE). The Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT)’s role is to certify and monitor the performance of the companies from the private sector that have joined the program. The policy targets to create 14 million new user base for Internet and provides for building the foundation of Egypt’s Information society initiative.

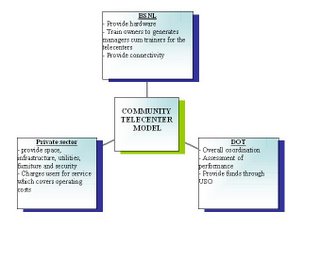

The “IT Clubs” model is another Public Private Partnership to bring affordable Internet access throughout the country to those who cannot afford to own a PC.. The model was developed to offer a communal solution to one of the biggest problem encountered by emerging economy to develop Information society i.e. the problem of affordability, accessibility and awareness. MCIT is forming partnerships with Egyptian and international entrepreneurs to accelerate the rate of expansion of IT clubs, which currently number more than 1000. IT clubs are now extending their services by providing library in each club, providing e-government services, providing e-learning services etc.

If India has to consolidate its positions as a leading hub of communication systems & IT enabled services and has to establish itself as a leader in new disciplines such as bioinformatics and biotechnology, it has to quickly adopt the successful policy initiative models from the developing and developed world. Only then, ongoing IT process in India can transform into a “True Revolution”.

INTRODUCTION

India, the second largest populated country of the world, is predominantly rural in nature. Of the 1.027 billion Indians, 741 million live in 638635 villages scattered all across the country. The population density in rural India is around 300 per sq km , which is quiet high in comparison with most of the other countries. Despite this the socio-economic conditions of most of the villages has been pathetic. The literacy rate in rural parts of India is 49.4% as compared to 70% in urban India. The lopsided development is further suggested by the fact that three out of every four villages do not even have the primary health centre. Over 70 % of the rural population contributes to only 24% of GDP. Poor infrastructure and lack of banking facility have further hampered the economic growth in rural areas. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) have been seen as a major tool that can address many of these socio-economic issues. Worldwide, lives of millions have been benefited by use of ICT tools. India is suppose to be an IT super-power and a major recruiting ground for ICT professionals. Being the force behind many of the ICT projects implemented even in rural areas of developed countries, these professional have been instrumental in bringing around considerable change in rural lives globally. Strangely the same could not be achieved in India due to the absence of basic telecommunication infrastructure. India has a large number of rural villages that do not have telephone connectivity. Over the period of time, this has resulted in a glaring digital divide between rural and urban India. Bridging this digital gap requires considerable investments.

Telecommunication, along with electricity and transport, has been identified as key infrastructure sector for building tomorrows India. The sector, better known globally as Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), is one of the prime support services needed as stimulus for rapid growth and modernization of various sectors of the economy and is also vital for social development of the country. Surveys have shown that every single effect in the telecom sector has many fold effect in the economy of a country. Another key area to attain the goal of accelerated economic development and social change is the provision of telecom services in rural areas. The aggressive expansion of Telecom infrastructure in geographically remote parts of the country is very much essential for unleashing the latent economic energies and market forces in these regions.

INTRODUCTION

India, the second largest populated country of the world, is predominantly rural in nature. Of the 1.027 billion Indians, 741 million live in 638635 villages scattered all across the country. The population density in rural India is around 300 per sq km , which is quiet high in comparison with most of the other countries. Despite this the socio-economic conditions of most of the villages has been pathetic. The literacy rate in rural parts of India is 49.4% as compared to 70% in urban India. The lopsided development is further suggested by the fact that three out of every four villages do not even have the primary health centre. Over 70 % of the rural population contributes to only 24% of GDP. Poor infrastructure and lack of banking facility have further hampered the economic growth in rural areas. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) have been seen as a major tool that can address many of these socio-economic issues. Worldwide, lives of millions have been benefited by use of ICT tools. India is suppose to be an IT super-power and a major recruiting ground for ICT professionals. Being the force behind many of the ICT projects implemented even in rural areas of developed countries, these professional have been instrumental in bringing around considerable change in rural lives globally. Strangely the same could not be achieved in India due to the absence of basic telecommunication infrastructure. India has a large number of rural villages that do not have telephone connectivity. Over the period of time, this has resulted in a glaring digital divide between rural and urban India. Bridging this digital gap requires considerable investments.

Telecommunication, along with electricity and transport, has been identified as key infrastructure sector for building tomorrows India. The sector, better known globally as Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), is one of the prime support services needed as stimulus for rapid growth and modernization of various sectors of the economy and is also vital for social development of the country. Surveys have shown that every single effect in the telecom sector has many fold effect in the economy of a country. Another key area to attain the goal of accelerated economic development and social change is the provision of telecom services in rural areas. The aggressive expansion of Telecom infrastructure in geographically remote parts of the country is very much essential for unleashing the latent economic energies and market forces in these regions.

Though disparities between the telecom infrastructure of the urban and rural areas are common to all countries, in India this is a continuing source of concern because of declining trend and will become further aggravated unless innovative policies are evolved to accelerate the rural telecom development. For the same it is necessary to understand the underlying dimensions of the low tele-density in rural India.

REASONS FOR POOR TELE-DENSITY IN RURAL INDIA

The rural areas are characterized by sparse population having poor purchasing power. The basic infrastructure viz. electricity and transport is inadequate. In such areas the public interest in telecom facility is caught in a typical cart and horse situation where in absence of telecommunication facility the public interest has not been stimulated. It is not surprising that out of 6,07,491 village is India only about 0.53 million have direct access to telephone facility. With the advent of liberalization in telecom sector all private and government based telecom companies have been concentrating on providing services in big cities and towns to maximize profits. Presently the provision of telecom services in rural areas is typified by high set up cost and low returns. These typical socio-economic conditions, coupled with poor geographical spread has resulted in declining growth of telecommunications infrastructure in rural India. Though investment in telecommunication infrastructure has jumped from 3.6 percent of GDP in seventh plan to 13% of GDP in Ninth Plan, half of the total telephones in India are concentrated in Metropolitan and 100 other capital/commercial cities.

REASONS FOR POOR TELE-DENSITY IN RURAL INDIA

The rural areas are characterized by sparse population having poor purchasing power. The basic infrastructure viz. electricity and transport is inadequate. In such areas the public interest in telecom facility is caught in a typical cart and horse situation where in absence of telecommunication facility the public interest has not been stimulated. It is not surprising that out of 6,07,491 village is India only about 0.53 million have direct access to telephone facility. With the advent of liberalization in telecom sector all private and government based telecom companies have been concentrating on providing services in big cities and towns to maximize profits. Presently the provision of telecom services in rural areas is typified by high set up cost and low returns. These typical socio-economic conditions, coupled with poor geographical spread has resulted in declining growth of telecommunications infrastructure in rural India. Though investment in telecommunication infrastructure has jumped from 3.6 percent of GDP in seventh plan to 13% of GDP in Ninth Plan, half of the total telephones in India are concentrated in Metropolitan and 100 other capital/commercial cities.

The private and now even public telecom operators are not willing to set up of infrastructure in such sparsely populated areas because of the costs involved. To add to injury, the returns are not very sustainable and will remain low in near future till the tele-density improves. The last mile connectivity costs have remained one of the biggest hurdles in providing cheap communication facilities to users. Those who have already built some network in rural areas are not willing to share it with others as they see it as big first move competitive advantage. Poor transportation facilities, irritant power supply, unavailability of spares and technical man-power has resulted in high maintenance costs which further increases losses to operators in such areas.

STEPS TAKEN TILL DATE TO INCREASE RURAL TELE-DENSITY

Before liberalization, universal service objectives have been met by the DOT through a series of programs like Long Distance Public Telephone Program (progressively increasing the scope to the provision of a public telephone within 5 kms of any habitation one telephone in a hexagon of size 5 Square Kilometers), Gram Panchayat Phone (one phone in each Gram Panchayat), and Village Public Telephone Program (one phone in each revenue village) to provide access to voice services. While liberalizing the access segment, post NTP 1994, specific VPT roll out obligations were specified in the licenses.

Post liberalization the various “state interventions” or policy measures taken to increase tele-density in rural India can be grouped under various heads as follows –

1) Tariff Policy - Rural & Urban fixed rentals were traditionally below cost. Mobile tariffs, when specified earlier, were cost based. In 2003, urban fixed tariffs were forborne. However, rural fixed rentals are still regulated and range from Rs. 70 - 280 depending on the exchange capacity. The service provider is allowed to give lower tariffs under alternative tariff package.

2) USO Fund Policy - In 2002, Universal Obligation Service (USO) Fund was established to fund specific USO targets set by NTP 99. The USO levy is presently 5% of AGR and comes out of the license fees paid to the government. However, the implementation of Universal Service Obligation is through a multi-layered bidding process. The Fund is being administered by the Department of Telecom through Universal Service Fund Administrator. On 9th January 2004, the Indian Telegraph Act 1885 was amended to provide the USO Fund a statutory non-lapsable status. The Act states -

“Universal Service Obligation” means the obligation to provide access to basic telegraph services to people in rural and remote areas at affordable and reasonable prices”. The USO aims to fund voice access in remaining villages, low speed data in 35000 villages, high speed data access in about 5400 villages, subsidy for DELs in rural and/or remote SDCAs (486 out of 2648) . At present about 5% of adjusted gross revenue is collected which is estimated at about Rs 3000 Crores for 2004-05. But the disbursement of fund has been an issue. The USO administration has been slow in disbursement of fund and is virtually sitting on more than Rs 30 billions. This has resulted in cautious approach by telecom operators in rolling out their rural obligations.

Liberalization/Competition - Intense competition in mobile services is forcing operators to bring down tariffs and expand coverage to hitherto untouched rural areas. Presently the tariffs for mobile telephony in India have all the more turned one of the lowest in the world. Some reports suggest that tariffs in India are about 50% lower than that of its neighbors, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. This is the reason for high mobile growth in that country. The number of telephones in India, the world’s fifth-largest telecom market, has crossed 100 million connections and the customer base is likely to touch 250 million by 2007. The rates seem to be further going south wards. In April 2005 - a one-minute, local calls costs just 3 cents compared with 8 cents earlier. The regulator in India – TRAI has stopped regulating the rates of mobile services in India for almost couple of years and the prices are forborne. Thus we see that competition has really made the Indian mobile market affordable to citizens and have encouraged the operators to set up their network in rural India.

3) Termination charges - Rural termination charges have been kept same as urban termination charge to give boost to rural telephony

4) Access deficit charges (ADC) – This is a charge imposed to cover the deficits in provision of fixed lines in rural and urban areas. Funding to the extent of Rs 53.40 billions per annum has been provided to state PSUs through collection of ADC. Recently ADC has been reduced from 30% of the sectoral revenue to 10% to make services more competitive.

5) Government funding – Government has provided license fees reimbursement to BSNL (Rs 23 Billions) in lieu of commitment to provide 10 lakh rural DELs. Encouraged by such supports the state owned incumbent operator is planning to invest Rs 84 Billions for expansion of its network in rural areas.

6) Roll-out obligations – Government of India has fixed certain roll-out obligations to all operators to ensure that their services are mandatorilly started in rural areas. For e.g. access providers have to cover 50% of District Head Quarters, National Long Distance Operators have to setup Point Of Presences in every Long Distance Charging Areas (LDCA). The revised roll out obligation for National Long Distance (NLD) services are also under consideration.

Though, some advancement has been made towards improving the rural connectivity, the gains are marginal. A lot needs to be done and that too at much greater pace. If information and Communication Technology has to play a major role in improvement of the life of India’s rural population, the telecom infrastructure backbone has to be considerably strengthened in these areas.

DIGITAL DIVIDE – THE INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

The problem of digital divide is not unique to India but exists in almost all countries of the world in one form or other. Having looked at the severity of the problem in India, the reasons for its existence and the efforts done till date for bridging the digital divide, it becomes logical to scan the world horizon and look for policy initiatives taken in emerging economies for addressing the problem and implement them in India after customizing them to suit the local needs.

The ICT development indices report released by United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that during 1995-2002 countries like Egypt, Mexico, China & South Korea have shown remarkable progress in increasing the penetration of ICT amongst masses. Scanning the world horizon, we find that rapid growth in telecommunications have been either demand driven like in China or state-pushed like in South Korea and Egypt. The growth of ICT in urban India has been mainly demand driven. To increase the penetration of ICT in rural India will require greater policy leadership and initiative from state. Overall ICT usage and penetration in the country has still lagged behind international averages. At today’s levels, though, Indians are expected to pay 60 times more than subscribers in Korea for the same throughput, which translates to 1,200 times more when considering affordability measures based on GDP per capita comparison. As recently as 1996, Korea had internet subscriber penetration under 2%, and broadband reached close to 1% penetration only in 1999. In the five years since, however, broadband has become a way of life for Koreans, and it permeates in everything they do. Today, almost 80% of households have broadband connections, and in 2002, US$148 billion, nearly 30% of their GDP, was transacted on the internet. China has also launched a major broadband expansion program. The success in other countries in making telecom services as the basic platform on which economic and commercial growth is achieved, can also be replicated in India, particularly for rural areas.

Though, some advancement has been made towards improving the rural connectivity, the gains are marginal. A lot needs to be done and that too at much greater pace. If information and Communication Technology has to play a major role in improvement of the life of India’s rural population, the telecom infrastructure backbone has to be considerably strengthened in these areas.

DIGITAL DIVIDE – THE INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

The problem of digital divide is not unique to India but exists in almost all countries of the world in one form or other. Having looked at the severity of the problem in India, the reasons for its existence and the efforts done till date for bridging the digital divide, it becomes logical to scan the world horizon and look for policy initiatives taken in emerging economies for addressing the problem and implement them in India after customizing them to suit the local needs.

The ICT development indices report released by United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that during 1995-2002 countries like Egypt, Mexico, China & South Korea have shown remarkable progress in increasing the penetration of ICT amongst masses. Scanning the world horizon, we find that rapid growth in telecommunications have been either demand driven like in China or state-pushed like in South Korea and Egypt. The growth of ICT in urban India has been mainly demand driven. To increase the penetration of ICT in rural India will require greater policy leadership and initiative from state. Overall ICT usage and penetration in the country has still lagged behind international averages. At today’s levels, though, Indians are expected to pay 60 times more than subscribers in Korea for the same throughput, which translates to 1,200 times more when considering affordability measures based on GDP per capita comparison. As recently as 1996, Korea had internet subscriber penetration under 2%, and broadband reached close to 1% penetration only in 1999. In the five years since, however, broadband has become a way of life for Koreans, and it permeates in everything they do. Today, almost 80% of households have broadband connections, and in 2002, US$148 billion, nearly 30% of their GDP, was transacted on the internet. China has also launched a major broadband expansion program. The success in other countries in making telecom services as the basic platform on which economic and commercial growth is achieved, can also be replicated in India, particularly for rural areas.

Egypt also has a strong tradition of central government and reliance on government to provide services and policy leadership. During 1995 to 2002, Egypt rose strongly in ICT diffusion ranking from 154th position to 112th position worldwide despite the fact that its economy has suffered a slowdown and deterioration in economic conditions since 2000, which has led to reductions in real wages and consumer purchasing power. Egypt has encouraged investment in infrastructure and has been building public-private collaboration in ICT deployment. Its experiment with models of shared public access in the IT Clubs can be replicated in developing countries like India where the PC penetration is still dismal.

BRIDGING THE DIVIDE – LESSONS FROM EGYPT

Arab Republic of Egypt, the most populated Arab state, has 55% of its population living in rural areas (as per latest census estimates of 1999) . With GDP growth rate averaging above 5, Egypt is ranked at 119th as compared to 127th of India in United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) Human Development Index(HDI) . After formation of Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (MCIT) in 1999, Egypt has raced ahead on its path of Information society initiative. The Telecom and Information Technology policy of Egypt has tried to bridge the digital divide within the country and its initiatives to empower the citizens with information has evolved around three basic policy pillars

BRIDGING THE DIVIDE – LESSONS FROM EGYPT

Arab Republic of Egypt, the most populated Arab state, has 55% of its population living in rural areas (as per latest census estimates of 1999) . With GDP growth rate averaging above 5, Egypt is ranked at 119th as compared to 127th of India in United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) Human Development Index(HDI) . After formation of Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (MCIT) in 1999, Egypt has raced ahead on its path of Information society initiative. The Telecom and Information Technology policy of Egypt has tried to bridge the digital divide within the country and its initiatives to empower the citizens with information has evolved around three basic policy pillars

1. Heavy emphasis on research and development in traditional and new industries to allow Egypt to become and remain a world class competitor. Research and development centres of excellence have been established to bring together professionals, private sector initiatives and educational establishments.

2. To allow Egypt to become an attractive foreign investment hub, favorable regulatory policies have been put in place. The foreign investment inflow has not only been source of employment generation but is also benefiting Egypt through technology spin – offs. Setting up of National Telecom Regulatory Authority (NTRA) and Initial Public Offering (IPO) of Telecom Egypt are part of such initiatives for freer market.

3. The third and most crucial policy initiative has been of providing total access of the Internet and related services to encourage entrepreneurs and markets to fulfill their potential. This policy of e-Access has concentrated on ICT capacity building in the community by reaching out to the poorer and rural areas.

The third pillar of Egypt’s ICT policy has been implemented through several micro level programs which are based on three key success factors for ICT diffusion amongst masses i.e. awareness, accessibility and affordability.

These micro-level e-Access programs are uniquely developed to suit the Egyptian conditions and are of special interest to emerging economies like India. These programs have helped in bridging the digital divide within Egypt’s industries, people, and wide ranging cultures and have helped the country “to move forward as a whole, and not just in certain sectors.” These micro-level policies or programs combine the imaginative use of emerging technologies with creative Public Private Partnerships and Multi Stakeholder Partnerships to accelerate development. The e-Access policies have been built over the growth of telecom infrastructure and guarantee universal, easy, affordable and rapid access for all citizens to ICT. They have become instrumental in stimulating awareness of the potential uses and benefits of ICT to masses and classes alike. The initiative not only focuses on hardware and software but also emphasizes the development of flexible and innovative tools and channels. Of the various micro-level policy initiatives the two which can be considered to be of interest for implementation in India are -

The third pillar of Egypt’s ICT policy has been implemented through several micro level programs which are based on three key success factors for ICT diffusion amongst masses i.e. awareness, accessibility and affordability.

These micro-level e-Access programs are uniquely developed to suit the Egyptian conditions and are of special interest to emerging economies like India. These programs have helped in bridging the digital divide within Egypt’s industries, people, and wide ranging cultures and have helped the country “to move forward as a whole, and not just in certain sectors.” These micro-level policies or programs combine the imaginative use of emerging technologies with creative Public Private Partnerships and Multi Stakeholder Partnerships to accelerate development. The e-Access policies have been built over the growth of telecom infrastructure and guarantee universal, easy, affordable and rapid access for all citizens to ICT. They have become instrumental in stimulating awareness of the potential uses and benefits of ICT to masses and classes alike. The initiative not only focuses on hardware and software but also emphasizes the development of flexible and innovative tools and channels. Of the various micro-level policy initiatives the two which can be considered to be of interest for implementation in India are -